There [Aeneas] divided

The wine courtly Acestes had poured out

And given them on the Sicilian shore –

Full jugs of it – when they were about to sail.

Aeneid I. 195-7 (tr. Robert Fitzgerald)

If [a schoolteacher] is asked a random question while he’s heading for the hot baths or Phoebus’ spa, he must be able to identify Anchises’ nurse and to state the name and birthplace of the stepmother of Anchemolus and how long Acestes lived and how many jars of Sicilian wine he gave to the Trojans.

Juvenal, Satires VII. 232-6 (tr. Susanna Morton Braund)

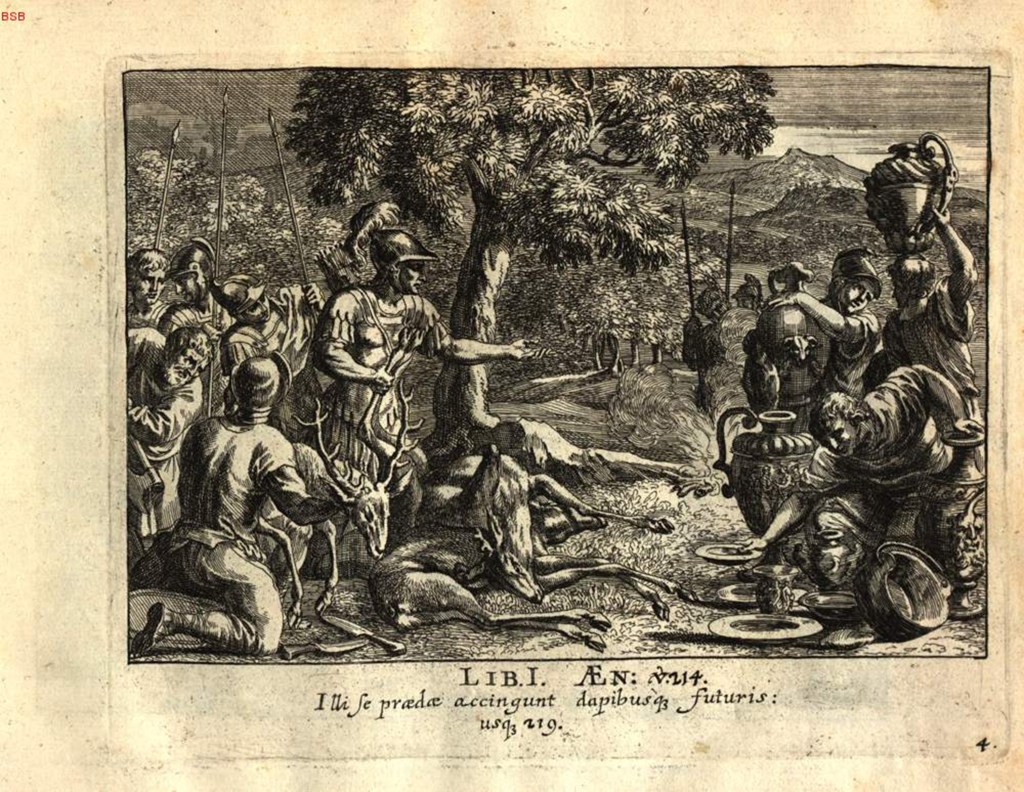

At the beginning of the Aeneid, tempest-tossed and driven to an unknown shore from Sicily, Aeneas and his men must have been both exhausted and starving. Aeneas, ever dutiful, ventures out to find meat for his men. He manages to shoot seven deer and “parcel out the game” equally to his seven ships’ worth of men. To make the feast truly epic, drinking is in order, and Virgil describes the uncorking (well, almost) in a syntactically convoluted passage. Word for word (Aeneid I. 195-7):

Wine good (bonus) which then in jars (cadis) had loaded Acestes

On the Trinacrian shore and had given to those departing (abeuntibus) the hero (heros)

[Aeneas] divides

“Good” and “the hero” both modify “Acestes,” “the Trinacrian shore” is a Greekism for “the shore of Sicily,” and “those departing” refers to Aeneas and his men. On the North African shore, Aeneas proceeds to divvy up, in other words, a parting gift from his fellow Trojan Acestes, a gift that he and his men had probably hoped to enjoy under better circumstances (perhaps even under a roof) in Italy.

So far, a lot to interest an imaginative reader or teacher; a lot, in fact, to interest even an unimaginative one. It is difficult to construe, it provides the first fleeting mention of Acestes (who appears briefly later in the work, when the Trojans return to Sicily), and it is loaded with loanwords from Greek (“jars,” “hero,” and “Trinacrian,” not to mention “Acestes,” are all of Greek origin).

In his satirical dialogue Charon, the humanist and diplomat Giovanni Pontanus (1426-1503) imagined a recently deceased, pedantic schoolteacher (grammaticus) named Pedanus, who, roaming the Elysian Fields, manages to buttonhole Virgil to ask him about these lines and is eager to report his findings to his former students. He can finally answer the questions that Juvenal imagined acquaintances asking a beleaguered schoolteacher on his day off (“Teacher, huh? Maybe you can tell me…”). Imagine an English teacher meeting Shakespeare, questioning him about religious anachronisms in King Lear (why does Lear swear by Jupiter?); imagine this same teacher expecting that his students might actually be interested in what he has learned. Here goes:

Mercurius: Quid tibi vis tam solus?

Pedanus: Te ipsum quaerebam, Maia genite.

Mercurius: Quanam gratia?

Pedanus: Oratum venio, quaedam meo nomine ut discipulis referas; quod te vehementer confido facturum, cum litterarum auctor atque excultor fueris.

Mercurius: Facile hoc fuerit; quamobrem explica quid est quod referam velis.

Pedanus: Virgilium nuper a me conventum dicito, quaerentique ex eo mihi quot vini cados decendenti e Sicilia Aeneae Acestes dedisset, errasse se respondisse; neque enim cados fuisse, sed amphoras; ea enim tempestate cadorum usum in Sicilia nullum fuisse; partitum autem amphoras septem in singulas triremes accessisseque aceti sextariolum, idque se compertum habere ex Oenosio, Aeneae vinario. Ex Hipparco autem mathematico intellexisse Acestem ipsum vixisse annos centum viginti quatuor, menses undecim, dies undetriginta, horas tris, momenta duo ac semiatomum.

Mercurius: Idem ego memini me ex Aceste ipso audire.

Mercury: What are you up to, all alone?

Pedanus: I was looking for you, son of Maia.

Mercury: To what end?

Pedanus: I have come to ask that you pass along some information to my students on my behalf; which I am sure you will be happy to do, since you were the one who founded and perfected literature.

Mercury: Easy enough – so explain what you would like me to pass along.

Pedanus: Tell (them) that I recently met with Virgil, and that, when I asked him how many jugs (cados) of wine Acestes had given to Aeneas as the latter was departing from Sicily, he told me that he [i.e. Virgil] had made a mistake – they weren’t jugs (cadi), but rather amphoras, since in that period in Sicily jugs were never used.1 He distributed seven amphoras, one to each trireme, to which was added a small pint of vinegar (sextariolum aceti), a fact which he had ascertained from M. de Vineux (Oenosius), Aeneas’ sommelier.2 Furthermore, from the mathematician Hipparchus [of Nicaea, c. 190-120 B.C.E.] he learned that Acestes lived for one hundred and twenty-four years, eleven months, twenty-nine days, three hours, and two fortieths of an hour plus a half-instant (momenta duo ac semiatomum).

Mercury: I remember hearing this from Acestes himself.

Source: Giovanni Pontano (1426-1503), Charon

- Throughout at least much of antiquity, the words cadus and amphora seem to have referred to very similar vessels. Part of the joke may be that in at least some forms of post-classical Latin cadus (per DMBLS) seems to have come to mean “cask, barrel,” a more modern kind of vessel for storing wine and other spirits. Perhaps Pedanus has pushed the shade of Virgil to distance the Aeneid even further from present-day realities by using a word (amphora) that is both transparently Greek (as cadus is not, even thought it is in fact derived from the Greek kados) and refers to something indisputably old-timey. ↩︎

- The name seems to be a joke, made up from Gk. oinos ‘wine.’ ↩︎